Up until around 2010, many startups would raise pre-product seed rounds using only an investor deck, idea, and the spark in their eyes. Those times are long gone. Today investors know that the cost of reaching a viable product (in many sectors) is low enough that serious founders will create their product, and initial traction, before seeking external funding.

There is merit in demanding a POC, MVP, or traction, but regretfully this means that many good ideas (albeit also bad ones) and good companies ultimately fail to reach the market. There are many entrepreneurs who cannot afford to stop working at their day-job, or have great marketing skills but do not have the technical skills to develop their initial product and fail to locate a suitable CTO. Others pursue their idea part-time and reach the market after four years instead of one, many times too late.

In general, the cost of bringing an average startup (software and simple hardware) to the MVP stage is $150K-$200K. This sum provides the necessary runway which includes minimum salaries for 2-3 technical founders (or outsourced development), some WeWork-like office space, and external consultants and service providers (e.g. UX, DevOps, business, and marketing). Small change in today’s $500K-$3M seed rounds.

However, getting external investment at this stage is impossible. Most founders will resort to raising money from the three F’s (Friends, Family, and Fools) or try to cut corners while bootstrapping to get a product out faster, rarely with positive results (lean methodology aside, shortcuts are not always a good thing, but that’s an article for another time). Most FFFs are not professional investors and don’t understand what it means to invest in a startup. Additionally, they cannot usually bring any true added value (aside from the invested capital) to the startup, only stress and pressure on the founders.

But are professional investors making the right choice in foregoing investment in pre-product companies? I argue that with the right methodology, these investments are financially better than later stage investments.

Some preliminary assumptions to start with

Let’s examine what happens to invested money during a startup’s life-cycle. We’ll look at the type of company that can get a start from $200K pre-seed investment, for example, a mobile app, Internet or simple IoT device. Next, let’s assume that following a $200K pre-seed round the company then raises $500K seed money, a $3M round A and an $8M round B. At each stage we are diluted by 20%. Finally, after doing everything right, the company is then sold for $80M (6-8 years later).

For simplicity’s sake we will not take into consideration things like anti-dilution, or preemptive rights to keep the equity holdings by investing more money in each round, as well as down rounds, wipe-outs of the cap table, restructuring or other nasty things that can wipe out all equity for investors who do not pay to play.

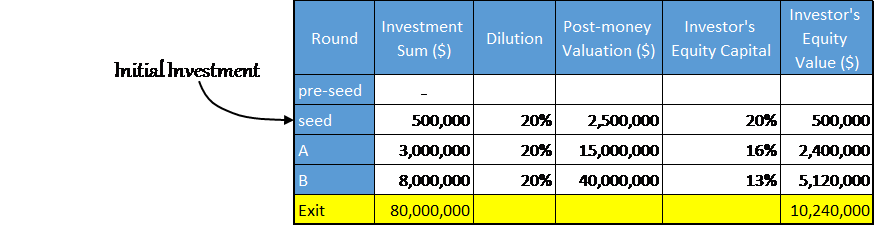

In our simple scenario, here’s what will happen to our invested money if we invest only in the seed stage:

Our gross revenue from this venture comes out to – $10.24M – $0.5M = $9.74M, or 19.5x ROI.

Not too bad.

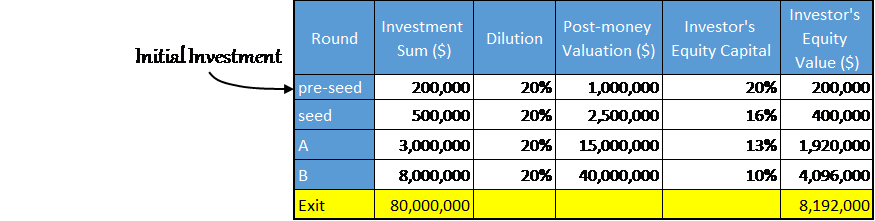

What would have happened if we invested in the pre-seed stage? Here’s what would happen to our money:

Our gross revenue this time comes to: $8.2M – $0.2M = $8M, or 40x ROI. Even taking into account that the time from investment to exit may be a year longer, this is a much better investment.

Now let’s assume we have $1M to invest in such companies. What are your options?

- Invest in two seed rounds of $500K for 20% of the company’s equity

- Invest in five pre-seed rounds of $200K for 20% of the company’s equity

Let’s examine each of these scenarios in more detail.

Scenario 1: You invested in two seed rounds of $500K

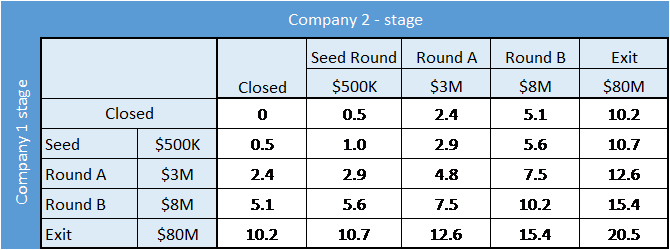

The following table shows your portfolio’s value (in millions of USD) depending on the stage of each the companies on have invested in:

How to read the table: each row and each column describes a stage in a company’s life-cycle (including shutting down, god forbid). The cell at the intersection of that row and column is the portfolio’s total value for these scenarios. That way if company 1 raised a Round B and the company 2 raised a round A the portfolio’s total value would be $7.5M.

The average portfolio value is $7.3M, a 7x return on investment, the maximum value is $20.5, i.e. about a 20x return on investment.

Scenario 2: You invested in five pre-seed rounds of $200K

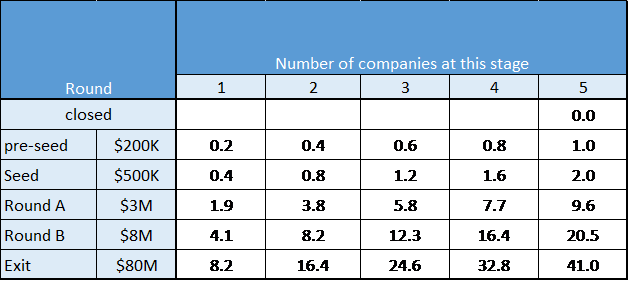

The following table shows the value of your portfolio depending on how many companies are at each stage.

How to read the table: each column shows the value of the portfolio if X (X being the number at the top of the column) is at this stage (for simplicity’s sake we will assume that all other companies have closed). Thus, for example, if 3 companies have been able to raise an A round (and 2 closed) then the total portfolio value would be $5.8M.

The average portfolio value is $8.5M, a more than 8x return on investment, the maximum value is $41M, i.e. about a 40x return on investment. Interestingly, even if you invest in only four companies (for a total investment of $800K), your average portfolio value is $7.4M, the same as in scenario 1, while the maximum value is $32.8M, a whopping 33x return on investment.

So what does this mean?

Basically, that if all things being equal, it could be a lot more profitable to invest in pre-product companies than in seed stage companies. So why don’t more investors actually follow this model of investing in pre-seed/pre-product companies?

Risk.

A recent CBinsights research showed the “venture capital funnel”, which displayed the number of startups that were able to attain funding during each stage of their life-cycle.

From 1,027 companies that received seed funding only 538 raised a second round or were acquired. That is a ratio of 52%, which means that 48% probably didn’t make it (I’m sure that a few became self-sustaining, but that is rare at this stage).

What happened to the failed 48%? Usually it’s a matter of product-market fit, a team that cannot execute properly or a bad business model.

Basically, the further on in the startup lifecycle you invest the lower your risk. Of course, your potential rewards are lower too. Thus, seed-stage companies present a bit less risk to the investor since they have at least managed to do one thing – create a product. And on the way to creating a product many things are resolved, especially the team’s real ability to execute.

So what we need to do is lower our risk, right?

So, in order to properly invest in pre-product companies, your main goal as an investor should be to mitigate as much risk as possible, at least to the risk level of a seed stage company. Conceptually this is a big gap (like going from kindergarten to grade school), but can be overcome at a relatively low cost.

VCs used to do lower their risk at this stage with internal pre-seed programs (a select few still do), which gave them a way to better vet the companies and maintaining an “option” for future investment in interesting companies. However in the past several years they have left this task to the various accelerator programs, who (in my opinion) have only been partially able to fill the gap.

Another option recently becoming more popular is equity crowd-funding, where the startups raise the first pre-seed round from a large group of small investors, each investing a few thousand dollars, and spreading the risk among them. These include companies like FundersClub and Wefunder in the US and ExitValley in Israel.

But what can a single smaller investor, one that invests $1M-$5M a year, do? Here’s an idea:

Create a pre-investment investment strategy

Allocate 20% of your investment budget for pre-investment vetting.

For each pre-product company you believe is interesting and shows potential, invest an initial $10,000 (potentially for a small 1%-2% stake in the company). These funds will be used to deliver the following information and results, a preliminary due-diligence of sorts:

- A clear product definition – What it is, what are the usage cases, a mockup and perhaps some feedback from potential customers.

- Thorough market research – on the company’s target market (definition, size, trends) and its competitors (today, tomorrow, status, business models, revenues).

- A valid plan of business – not a 25 page document (i.e. a “business plan”), but rather a few well thought out pages explaining how the business will evolve, from launch to success, with defined initial strategy for go-to market, basic financial assumptions and a two-year budget for the $200K investment

- Monetization strategy – One or more potential business models and their relevant financial models showing the assumptions and the potential upside.

The purpose of this stage is not only to understand the business opportunity, but also to see how the founders work – do they know how to get and explain the proper information? Do they make business sense? Do they understand their market and their product relation to it (aka product-market fit)? How do they work together? Are they flexible in their grasp of their business? You’d be amazed how much you can learn about people from a few meetings and some homework.

Once they pass this test, invest the full $200K pre-seed in the company and help them reach the seed stage.

This means that from a $1M budget you will have $200K for vetting 20 companies, and $800K for investing in four of them. You now have 4 portfolio companies and potentially a small stake in 16 more who may now have a better chance to raise some capital elsewhere.

Post-investment follow-up

After you have invested the $200K in the company, ensure constant contact with the company. Become part of their board and have a monthly meeting to see progress and be able to shift strategic directions as needed. However, do not be too hands-on. Be a mentor, direct and assist, do not manage the company. There is no surer way to kill a startup’s enthusiasm than to micro-manage the founders or force them in a direction that is not in sync with their vision.

Some investors may choose to have a professional represent them as a board member instead of spending so much time on their portfolio companies and receive periodic updates on the team and the direction of the company.

Bottom line

In doing these two relatively simple processes, you, the small investor, can increase your success rate and portfolio value. On an investment budget of $1M you are able to evaluate 20 companies, investing $10K in each, for a total of $200K, and investing the additional $800K in the four most promising companies ($200K in each) to bring them to the next stage in their life-cycle.

Your average portfolio value will still be $7.4M, but you can now reach an x33 return on investment, rather than “only” x20 as would be the case if you choose to invest in just two companies. You also have your figurative eggs in more figurative baskets.